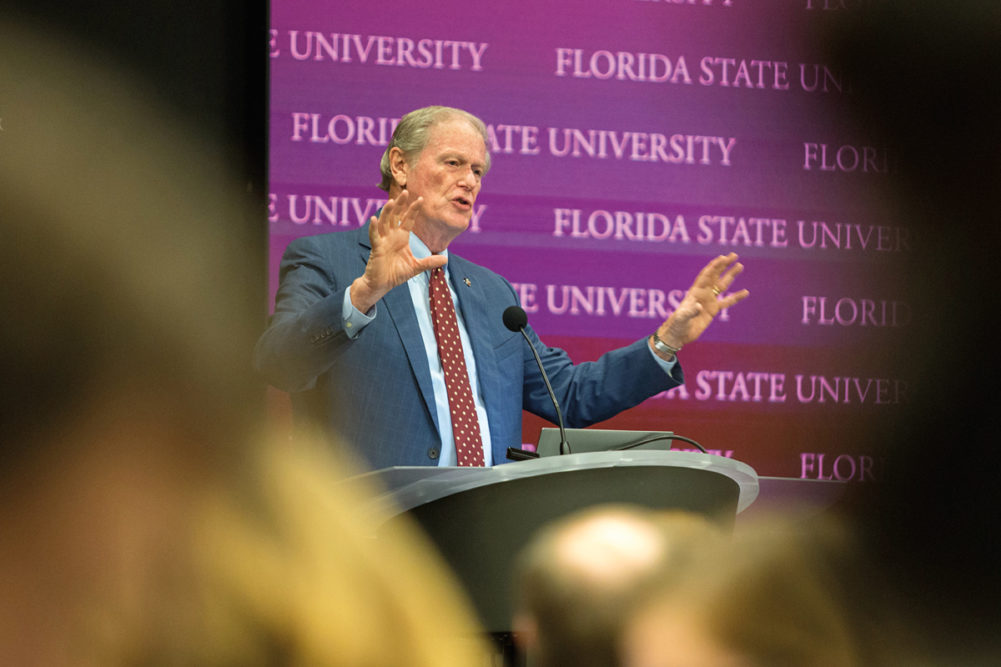

“When I started this job at age 70, I was enthusiastic about it — it was something I never dreamed I’d have the opportunity to do,” said John Thrasher, Florida State ’65.

Thrasher is the 15th president of Florida State University. His presidency is the capstone to a highly successful career as a businessman, lobbyist, lawyer and Florida legislator.

“This will be the last job — and it’s the best job I’ve ever had,” he said.

Before assuming his current role, Thrasher’s résumé lacked academic credentials. But his experience was the very reason he was considered for the position. In an era when many state legislatures are asking universities to do less with more, Thrasher’s fundraising prowess and proven ability to get things done at the state capital were exactly what the school’s trustees were looking for.

In addition, Thrasher had maintained strong ties to Florida State throughout his career. He earned his bachelor’s and law degrees from the school and was a strong advocate for his alma mater during his time in the Florida house and senate. He was the first chair of the school’s board of trustees, and he helped secure funding from the state to establish the university’s medical school.

Thrasher’s nomination was approved on Nov. 6, 2014, and since then he’s been laser focused on building Florida State into a national powerhouse.

By the start of the 2017-2018 school year, Florida State ranked No. 33 among all public universities on U.S. News & World Report’s list of top colleges. The school climbed 10 spots in Thrasher’s first three years as president. (Currently, the school is ranked at No. 26.)

Meanwhile, a record number of alumni were donating to the school, and Thrasher helped secure the largest private gift in Florida State’s history — $100 million.

When students arrived on campus in fall 2017, the school appeared to be firing on all cylinders. Thrasher was well on his way to completing a $1 billion fundraising campaign, and students were excelling as a result of smaller class sizes, new scholarships and a world-class faculty.

And what of fraternities? “I have to admit, when I got here, it was a secondary thing for me,” said Thrasher. “It just seemed like everything was OK. Then you have a major incident … and you realize you’ve got to take a step back and reflect on what we need to do.”

Student deaths are a wake-up call

On Friday morning, Nov. 3, 2017, 20-year-old Andrew Coffey was found lying unresponsive on a couch by one of his fellow Pi Kappa Phi pledge brothers.

The evening before had been the fraternity’s big brother night. And according to a lawsuit filed by Coffey’s parents, Coffey was pressured to drink an entire bottle of 101-proof bourbon. He later passed out and was “left all alone in a dark room surrounded by empty liquor and beer bottles, empty cups and vomit,” the lawsuit stated.

By the time Coffey was discovered the next morning, he didn’t have a pulse.

Coffey received medical treatment but was eventually pronounced dead at the scene. By the time an autopsy was performed, his blood alcohol level was 0.477 — almost six times the legal limit to drive. And it would have been even higher when he died.

The Monday after Coffey’s death, Thrasher suspended all 54 fraternities and sororities at Florida State and announced an alcohol ban that extended to more than 700 student organizations.

“This pause is needed to review and reflect on the loss of a young life, and to implement changes,” Thrasher said. “For this suspension to end, there will be a new normal for Greek life at the university. There must be a new culture, and our students must be full participants in creating it.”

Tragically, Thrasher had more than one student’s death on his mind when he announced the suspension.

Tim Piazza had died the semester before at Penn State after sustaining fatal injuries during an alcohol-fueled hazing ritual at the school’s Beta Theta Pi chapter home. And at Louisiana State, Phi Delta Theta pledge Max Gruver died from alcohol poisoning on Sept. 14 — a mere 50 days before Coffey’s death.

Then, just seven days after Thrasher announced the suspension, another young man was found dead at Texas State University. In a scene eerily reminiscent of Coffey’s death, Phi Kappa Psi pledge Matthew Ellis was found dead from alcohol poisoning the morning after he attended an off-campus fraternity party.

Across the country, there was a mounting sentiment that something drastic needed to be done.

Along with Florida State, university presidents at Penn State, Louisiana State and Texas State suspended their entire Greek systems. Later that month, other schools followed suit. Concerned about the health and safety of their students, leaders at the University of Michigan, Ohio State University and Indiana University each announced campus-wide suspensions for Greek life.

“We had four deaths at four different universities,” Thrasher said. “I think it’s caused us all to take a step back and really reflect on what value fraternities have and how we can make them better.”

Building a new normal

In the weeks and months following Coffey’s death, Thrasher met with students, faculty and staff, as well as peers from other universities, to consider how — and if — his school’s Greek system could move forward.

Then, on Jan. 29, 2018, nearly three months after suspending Florida State’s fraternities and sororities, Thrasher announced a long list of reforms.

The policy changes included mandatory participation in hazing prevention education for all Greeks, a limit on the number of social events chapters could host, and new restrictions on how and where alcohol could be served.

Additionally, all fraternities would be required to work with their national offices to conduct a membership review. The hope was that chapters could identify and preemptively remove members unwilling to commit to the school’s expectations.

And if any groups did slip up, Thrasher announced, Florida State would make that information public. The school is now publishing “scorecards” on its website that list chapter performance as well as any conduct issues. The goal is to hold chapters accountable, increase transparency, and help parents and potential members make better choices about Greek membership.

“We are going to monitor this closely,” said Amy Hecht, Florida State’s vice president for student affairs. “If we see that something isn’t working the way it should, we will consider changing it. This is a process, and we will be vigilant in making sure new guidelines and policies continue to protect the health and well-being of our students.” (In September 2018, Hecht joined SigEp’s National Board of Directors.)

Thrasher allowed fraternities to resume recruitment efforts and participate in philanthropic events. But the alcohol ban remained in effect until March 26, when Thrasher announced he would lift all sanctions and allow students to resume their normal activities under the new guidelines.

Meanwhile, Florida State is investing heavily in additional resources for Greek life. Before Coffey’s death, the school had allocated $300,000 annually to its Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life — a division responsible for supporting 22 percent of the school’s students. Starting in fall 2018, that budget increased by $1 million. The funding increase was approved by Florida State’s trustees and will be offset by a new $75 per-student fee paid by members of the school’s Greek community. The school will hire four additional Greek life staff members and introduce new programs focused on hazing prevention and leadership development.

Alcohol, hazing and the role of fraternities

Florida State’s new policies include tighter regulations on alcohol, and Thrasher hasn’t ruled out additional reforms. Still, he says he needs alumni and national fraternities to step up, too — especially when it comes to alcohol.

“I’d like to tell them to think about the role of alcohol in fraternities, and could we do without it? Could we do without it in the fraternity system altogether?” Thrasher asked. “I think that’s one of the primary problems that we have.”

Today, many national fraternities are asking those and similar questions.

In August 2017, SigEp’s undergraduate leaders voted to remove alcohol from all chapter homes. The legislation provided a three-year timeline for chapters to comply with the new standard, and it called on the Fraternity’s leadership to lobby peer organizations to adopt similar policies.

Since then, Beta Theta Pi and Delta Upsilon have both committed to supporting substance-free housing by August 2020, and Phi Kappa Psi has announced an immediate ban on hard alcohol.

And while these decisions represent a major shift for Greek life, the four fraternities aren’t alone in their efforts. For decades now, FarmHouse and Phi Delta Theta have banned alcohol from chapter homes. And so have all 26 members of the National Panhellenic Council, which includes most of the country’s large sororities.

With added pressure from leading fraternities and university administrators, more groups are stepping up to address the problem of alcohol abuse.

In August 2018, members of the North American Interfraternity Conference passed legislation that will ban hard liquor from chapter homes and fraternity events unless it’s served by a licensed third-party vendor. The new policy applies to 66 national fraternities and will take effect on Sept. 1, 2019.

While Thrasher’s thankful more fraternities are taking on the issue of alcohol, he’s also eager to see them refocus on the positive aspects of Greek life.

“Going forward, for the next five or 10 years, I hope fraternities will become more interested in academics, service and certainly in leadership in the university.”

To make that happen, more groups are supporting experiences modeled after SigEp’s Balanced Man Program, which replaces pledging with a series of progressive challenges that help members fine-tune leadership and life skills.

Beta Theta Pi, Lambda Chi Alpha, Tau Kappa Epsilon, Delta Tau Delta, Sigma Nu, Phi Delta Theta, Sigma Alpha Epsilon and Phi Kappa Alpha have each adopted their own version of the program.

A coordinated, national effort among colleges

Fraternity might not have been top of mind for Thrasher during his first three years as Florida State’s president, but he’s now at the center of a movement that’s seeking to bring college presidents together around the issue.

Thrasher already had a working relationship with Penn State President Eric Barron when he reached out to him in 2017. Barron had served as president of Florida State from 2010 to 2014, and the two had become friends during that time.

Barron supported Thrasher when he chose to suspend Greek life at Florida State, and soon the pair began discussing a national effort to address the problems of hazing and alcohol abuse.

“The more we can get in front of others and tell them about what we’ve done, I think we’ll make a difference,” said Thrasher.

They brought Louisiana State President F. King Alexander into their discussions and, in April 2018, addressed a group of presidents and administrators from 31 colleges. The group met in Chicago at an event sponsored by Penn State, the University of Nebraska and the University of Iowa.

The three presidents discussed the reforms they had put in place and their ideas for a coordinated, national effort.

Thrasher, Barron and Alexander are each publishing information about Greek performance and conduct issues on their school’s websites, and Penn State is in the process of developing a national scorecard that would include Greek systems across the country. The aim is to increase transparency at all universities and hold national fraternities and sororities accountable for the behavioral trends seen across their chapters.

To Thrasher, these efforts are necessary to protect students as well as a system he believes in.

“I’m very pro-fraternity,” he said. “I was a member of the SigEp Fraternity here at Florida State — it’s a positive experience for me.”

But is Greek life sustainable in its current form?

“Not if we have more incidents like we had [in 2017],” said Thrasher. “Recruitment in fraternities for this year is down from last year overall — certainly down here at Florida State. And I don’t want that to happen. I want us to be robust. I want the fraternities to flourish.

“But I think they also have to understand the kind of things that happened [in 2017] — and the incidents that happened at several of our universities in the country — cannot go on. They cannot. We cannot sustain that.

“If that happens, I think the national fraternities will see that the numbers of young men and women who want to get into Greek life are going to go down. … I want them to refocus, and that’s what we’re asking them to do.”

Leave a Reply